Why Rush-Hour Traffic Isn’t the Best Way to Rank Urban Mobility

Focusing on the peak period, as the Texas A&M Transportation Institute does, can miss the big picture.

The lens you use to observe something says a lot about what you’ll see. If you examined the human condition only during the hours of 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., for instance, you might find a species that isn’t terrible productive for a full third of the day. Your response might even be to call for the elimination of sleep as a way of improving economic growth.

The Texas A&M Transportation Institute, which puts out a regular ranking of rush-hour traffic congestion in U.S. metros, suffers from a similar myopia. It’s true that morning and evening commutes are a special form of hell with negative impacts on health and well-being. But by focusing on the narrow window of the peak period, the institute’s “Urban Mobility Scorecard,” as this year’s version is called, doesn’t actually do a good job scoring urban mobility—and instead arrives at some solutions that could hurt it.

Take your typical vision of bumper-to-bumper rush-hour traffic. The simplest conclusion here—beyond that the world enjoys self-inflicted torture—is that we need to build more highway lanes. That’s indeed a strategy the institute has embraced in the past; here’s Tim Lomax, one of the report’s main contributors, speaking to the Washington Post after the release of the 2011 ranking (spotted byGreater Greater Washington):

“You can do little things like stagger work hours, fix traffic-light timing and clear wrecks faster, but in the end, there’s a need for more capacity.”

Thing is, we know what happens when you reflexively expand capacity to fix traffic congestion: you do help things, but only temporarily. Inevitably, and before too long, congestion returns and you’re once again asking the same questions about how to handle it. As Robert Puentes of Brookings points out, the urban mobility report itself speaks to this process of “induced demand,” whereby commuters take to their cars once more lanes are available:

Since 1994, all but one of the top 100 places studied by the Texas A&M researchers saw congestion get worse, as measured by their Travel Time Index. Yet during that time, 92 of these places saw an increase in the amount of roadway miles per capita. … Yes, more road building in order to try to move vehicles faster often makes traffic worse.

Relying on highway expansion creates problems beyond more traffic—namely, a strain on transportation funding. Building new roads not only costs construction money now but it costs maintenance money later; a general failure to prepare for this full lifecycle of expenses explains much of America’s current infrastructure crisis. Additionally, in allotting so much money to the few-hour window that is rush-hour, local government finds itself without sufficient resources to provide mobility to the other 80 percent of travel that occurs outside the peak.

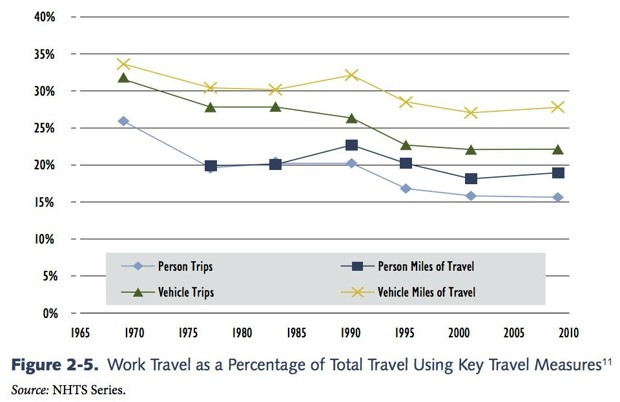

So by reducing urban mobility to rush-hour commuting, you’re missing the 20-some hour window of the day where metro areas have an underused (if not ghostly) roadway system as well as an underfunded city transit system—whose poor performance ironically leads more people to rely on cars. If you examined the traffic situation during this lens, you’d reach a much different set of conclusions.

Again, that’s not to say rush-hour traffic isn’t an economic drain or an emotional drag; it truly is. But it’s not entirely clear that commuter traffic is getting much worse over time. Joe Cortright at City Observatory, who has diligently tracked critiques of the mobility report, suggests the actual increase in congestion between now and 2030 will be a “trivial” 25 seconds per average commute trip.

The Texas institute predicts a much greater rise: something on the order of an hour or so a year. But that’s largely because the report relies on driving patterns from 2000 to 2005, the years immediately before most experts conclude that U.S. mileage trends peaked. Over at the Frontier Group, Tony Dutzik charts the years used for this forecast (below, in red), and explains that the future being outlined here essentially pretends (his emphasis) “that the last decade didn’t happen”: